Sport Leicht — Rennen

The Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR (W196S) was an iconic 2-seat sports racer that took sportscar racing by storm in 1955, winning that year’s World Sportscar Championship before a catastrophic crash and fire at Le Mans ended its domination prematurely.

Designated “SL-R” (for Sport Leicht-Rennen, eng: Sport Light-Racing, later condensed to “SLR”), the 3-liter thoroughbred was derived from the company’s Mercedes-Benz W196 Formula One racer. It shared most of its drivetrain and chassis, with the 196’s fuel-injected 2,496.87 cc straight 8 bored and stroked to 2,981.70 cc and boosted to 310 bhp (230 kW).

The W196s monoposto driving position was modified to standard two-abreast seating, headlights were added, and a few other changes made to adapt a strictly track competitor to a 24-hour road/track sports racer.

Two of the nine 300 SLR rolling chassis produced were converted into 300 SLR/300 SL hybrids. Effectively road legal racers, they had coupé styling, gull-wing doors, and a footprint midway between the two models.

When Mercedes canceled its racing program after the Le Mans disaster, the hybrid project was shelved. Company design chief Rudolf Uhlenhaut, architect of both the 300 SLR racer and the hybrids, appropriating one of the leftover mules as his personal driver. Capable of approaching 290 km/h (180 mph), the Uhlenhaut Coupé was far and away the fastest road car in the world in its day.

Name

In spite of the “300 SL” in its name and strong resemblance to both the streamlined 3-liter straight 6 1952 W194 Le Mans racer and the iconic 1954 300SL (W198) Gullwing road car the W194 spawned, the 1955 300 SLR was not derived from either. Instead, it was based on the wildly successful 2.5-liter straight 8 1954–1955 Mercedes-Benz W196 Formula One champion, with the W196’s engine enlarged to 3.0 liters for the sports car racing circuit and designated “SL-R” for Sport Leicht-Rennen (eng: Sport Light-Racing), later condensed to “SLR”. All were the work of Mercedes’ prodigious design chief Rudolf Uhlenhaut.

“We are driving a car which barely takes a second to overtake the rest of the traffic and for which 120 mph on a quiet motorway is little more than walking pace. With its unflappable handling through corners, it treats the laws of centrifugal force with apparent disdain.”

— Motor Trend

Design

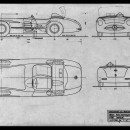

The 300 SLR was front mid-engined, with its long longitudinally mounted engine placed just behind the front axles instead of over them to better balance front/rear weight distribution. A welded aluminum tube spaceframe chassis carried ultra-light Elektron magnesium-alloy bodywork, which contributed substantially to keeping dry weight to a remarkably low 1,940 lb.

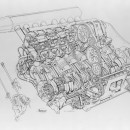

Power

The 2,496.87 cc straight-8 of the W196 Formula One car was bored and stroked to 2,981.70 cc, boosting output from 290 bhp at 8,500 rpm to about 310 horsepower at 7,400 rpm, depending on intake manifold. Maximum torque was 235 lb·ft at 5,950 rpm. Like the W196, the engine was canted to the right at 33-degrees to lower the car’s profile, resulting in slicker aerodynamics and a distinctive bulge on the passenger side of the hood shared with the streamlined Type Monza Formula one car.

To reduce crank flexing, power takeoff was from the center of the engine via a gear rather than at the end of the crankshaft. Other notable features were desmodromic valves, and mechanical direct fuel injection derived from the high-performance V12 used on the Messerschmitt fighter during World War II.

Fuel

Fuel was a high-octane mixture of 65 percent low-lead gasoline and 35 percent benzene; in some races, alcohol was also used to further boost performance. As a rule, the car left the starting line with 44 gallons and more than nine of oil on board, although Moss and Jenkinson began their assault on the 1955 Mille Miglia with as much as 70 gallons of fuel.

Gallery

Click any image below for larger view

All images Copyright © 2015 Mercedes-Benz

Suspension

To enhance stopping power extra wide diameter drum brakes too large to fit inside 16″ wheel rims were used, mounted inboard with short half shafts and two universal joints per wheel. Suspension was four-wheel independent. Torsion bars fitted inside the frame’s tubes were used in the double wishbone front.

To prevent cornering forces from raising the car, as occurs with short swing axles, the rear used a low-roll center system featuring off-centered beams spanning from each hub to the opposite side of the chassis crossing one-another over the centerline. Nevertheless, snap-oversteer could be still a notable problem at speed.

Wind brake

At Le Mans in 1955, the 300 SLRs were also equipped with a large rear mounted “wind brake” that hinged up above the rear deck to slow the cars at the end of the fast straights. The idea came from director of motorsports Alfred Neubauer, who’d been seeking to reduce wear on the huge drum brakes and tires during long-distance endurance races where cars repeatedly had to decelerate from 180 mph to as little as 25 mph. In tests the light-alloy spoiler slowed the car dramatically and improved cornering, helping to compensate for the superior new disc brakes of the SLR’s main rival Jaguar D-type.

Room for two

The SLR had a second seat for a co-driver, mechanic or navigator, depending on the race. As it turned out, it was only needed during the Mille Miglia, after which the 1955 Carrera Panamericana was cancelled due to the Le Mans accident. On short circuits such as the Targa Florio the extra seat was covered and passenger windshield removed to improve aerodynamics.

A total of nine W196S chassis were built.

Racing record

Stirling Moss drives former Mercedes racing teammate Juan Manuel Fangio’s Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR at the Nürburgring in 1977

Mercedes team driver Stirling Moss won the 1955 Mille Miglia in a 300 SLR, setting the event record at an average of 97.96 mph over 990 miles. He was assisted by co-driver Denis Jenkinson, a British motor-racing journalist, who informed him with previously taken notes, ancestors to the pacenotes used in modern rallying. Teammate Juan Manuel Fangio was second in a sister car.

The 300 SLRs later scored additional 1-2 world championship wins in the Tourist Trophy at Dundrod, Ireland, the Eifelrennen at the Nürburgring in Germany, and Targa Florio in Sicily, earning Mercedes victory in the 1955 World Sportscar Championship. Further non-championship trophies were also scored at the Eifelrennen in Germany, and Swedish Grand Prix.

“The greatest sports racing car ever built — really an unbelievable machine.”

— Stirling Moss

Tragedy at Le Mans

However, these impressive victories became overshadowed at Le Mans when the once again leading 300 SLRs were withdrawn after a horrific accident involving a team car driven by Pierre Levegh. Even with the innovative wind-brake, the car’s drum brakes had been unable to prevent Levegh from rear-ending an Austin-Healey, causing his car to become airborne.

Upon impact, the ultra-lightweight Elektron bodywork’s high magnesium content caused it to ignite and burn in the ensuing fuel fire. Compounding it, an uninformed race fire crew initially tried to extinguish it with water, only making it burn hotter. Eighty-four spectators and Levegh lost their lives in what remains the highest-fatality accident in the history of motorsport. Mercedes immediately withdrew from race competition, a ban which lasted three decades.

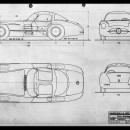

The Uhlenhaut Coupé

The road-legal 300 SLR racer known today as the Uhlenhaut Coupé was once the personal driver of its designer, Mercedes motorsport chief Rudolf Uhlenhaut.

Prior to the Le Mans accident he had ordered two of the nine W196s chassis built to be set aside for modification into an SLR/SL hybrid. The resulting coupé featured a slightly widened version of the SLR’s chassis, with signature ‘gull-wing’ doors still needed to clear its spaceframe’s high sill beams.

Before the project could be seen through, however, Mercedes announced a planned withdrawal from competitive motorsport at the end of 1955, in the works even before Le Mans. The hybrid program was abandoned, leaving Uhlenhaut to appropriate one of the leftover mules as a company car with only a large suitcase-sized muffler added to dampen its near-unsilenced exhaust pipes.

With a maximum speed approaching 180 mph, the 300 SLR Uhlenhaut Coupé easily earned the reputation of being the era’s fastest road car. A story circulates that running late for a meeting Uhlenhaut roared up the autobahn from Munich to Stuttgart in just over an hour, a 137-mile journey that today takes two-and-a-half.

Reviews

US auto enthusiast magazine Motor Trend road tested the car, as did two English journalists from Automobile Revue, who spent more than 2,000 miles behind its wheel. After a high-speed session at four o’clock in the morning on an empty section of autobahn outside Munich the latter wrote: “We are driving a car which barely takes a second to overtake the rest of the traffic and for which 120 mph on a quiet motorway is little more than walking pace. With its unflappable handling through corners, it treats the laws of centrifugal force with apparent disdain.”

Their only regret was that “we will never be able to buy [the car], which the average driver would never buy anyway.”

The Uhlenhaut Coupé has been preserved by Mercedes and is displayed at its corporate museum in Sindelfingen near Stuttgart. It’s unknown what became of its sibling.

Sources

- Mercedes-Benz

- Wikipedia

- NetCarShow.com

- Supercars.net